Environment

Short Takes

Georgia’s new data center rule increases local controlDecember 1, 2025

By David Pendered

July 24 – In a 1791 account of Muscogee (Creek) mythology, the Okefenokee Swamp is described as a sort of Shangra-La, an inaccessible place of rich resources, beautiful women and fierce warriors.

This story concludes with the entire written description of the Muscogee Nation’s relation with the swamp, as recounted by William Bartram, a Quaker natural scientist, in his expansive 1791 memoir that chronicles his four-year journey through the Southeast, The Travels of William Bartram. This story concludes with a commentary on Bartram’s report by the book editor for this 1958 edition, produced by Yale University.

Bartram’s account of the Muscogee Nation’s relation to the swamp has taken on new relevance in light of the latest proposal to extract wealth from the swamp’s environs. Twin Pines Minerals, LLC seeks to dig strip mines outside the southeastern border of the swamp to extract sands that contain titanium, which has multiple industrial uses. Tracts associated with the project exceed 12,000 acres near the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, according to a report by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps issued an order in June that halted the review of the permit application and compelled the involvement of the Muscogee (Creek) in discussions over the proposal. The civilian administrator who issued the ruling was strongly supported by the Senate, which voted to confirm Mike Conner’s appointment by a vote of 92-3, with his nomination endorsed by the National Audubon Society and a Republican senator who backs the Dakota Access Pipelines.

Twin Pines responded to Conner’s order by filing a federal lawsuit to block the Corps’ action. The latest development is Twin Pines’ motion of July 8, which asks a judge to temporarily halt the Corps from enforcing the order, according to a motion filed in the U.S. District Court’s Southern District, in Waycross.

Bartram traveled near the swamp as the nation was asserting its independence from England.

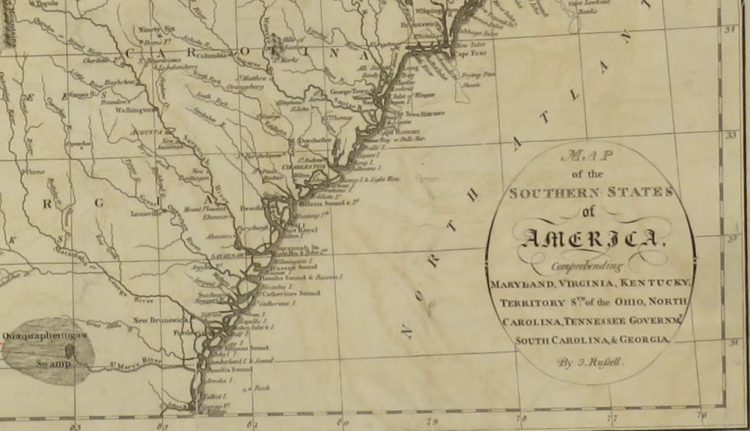

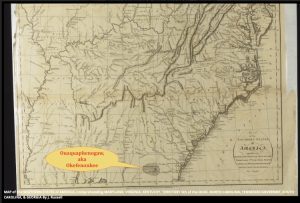

Bartram identifies the swamp by its name of the era, Ouaquaphenogaw, which also appears on a map produced in 1795 by a London cartographer, H. D. Symonds. Bartram reports the Muscogee (Creeks) portrayed the area as a “terrestrial paradise,” an “enchanting spot” with the “most valuable hunting grounds.” The women are “incomparably beautiful” and describe their husbands as “fierce men, and cruel to strangers.”

Ouaquaphenogaw was a place that, like other utopias, could not be found by the Muscogees who sought it. Their quest always ended with “never having been able to find that enchanting spot nor even any road or pathway to it.”

The book’s full title is in keeping with grandeur afforded travelers of the day: Travels through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, The Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogees, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians.

The title of the final section is in keeping with the period’s outlook on the native people: “Description of the Character, Customs and Persons of the American Aborigines….”

The Fulton County Library System has a copy available for checkout, the Naturalist Edition edited by Francis Harper and published in 1958 by Yale University Press. The book comes in at 727 pages, plus an afterward comprised of drawings of creatures including alligators and exotic species such as the Wattoola Great Savannah Crane, aka Florida Sandhill Crane, and the Crying Bird, aka Florida Limpkin. Photos dating to Harper’s retracing Bartram’s route in the 1930s show water hyacinth on the Alachua Savanna, in Florida, and rhododendrum growing at the “unparalleled cascade of Falling Creek,” in the Chattahoochee National Forest.

Bartram’s book doesn’t appear to have received direct coverage in recent days. WABE radio reporter Molly Samuel referenced the book, though not the author or title, in her July 6 report on a visit to the Okefenokee by members of the Muscogee Nation, ‘Our homelands are important’: Muscogee Nation works to deepen involvement with Okefenokee Swamp.

Verbatim from “The Travels of William Bartram”

The entire segment on the Okefenokee from The Travels of William Bartram is reprinted under the belief that this complies with fair use of the material. This section appears as one paragraph in the book. It is presented here in bite-size paragraphs that may be easier to read. From pages 17-18:

Verbatim from Harper’s commentary

Harper offers the following insights on Bartram’s report about the swamp. Again, this section is reproduced verbatim. From pages 339-340:

Son of the stranger! Wouldst thou take

O’er yon blue hils they lonely way,

To reach the still and shining lake

Along whose banks the west-winds play?

Let no vain dreams thy heart beguile,

Oh! Seek thou not the Fountain-Isle.”

0